- Home

- Martin Pistorius

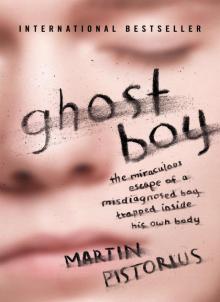

Ghost Boy

Ghost Boy Read online

Praise for Martin Pistorius and Ghost Boy

Reading this book brought me much closer to my son Logan, who has severe autism and is unable to speak. My understanding of Logan’s personal challenges were greatly clarified by Martin Pistorius’ ability to commit his experiences to writing. For anyone whose life has been touched by someone with communication challenges this book is a must!

— Glen Dobbs, president,

ProxTalker.com, LLC

Martin’s story not only typifies a person with great depth and humanity, but also of a great aptitude for life. This book is a must-read.

— Erna Alant, professor and

Otting Chair in Special

Education, Indiana

University, Bloomington,

USA

It is my sincere opinion that this book be required reading for anyone that works with children that have disabilities or is considering working in the field. Martin illustrates the person behind the disability as a “whole being” and it will change the way people with little experience in the field look at those with physical challenges.

— Karen Gorman, assistive

technology coordinator D75

NYCDOE

Ghost Boy is a book to open our minds and our hearts.

— Sue Swenson, former

US commissioner for

developmental disabilities

If you have time to read one book this year, I suggest that you chose Ghost Boy by Martin Pistorius. You may even come away with some questions about what it means to live a full life.”

— Diane Nelson Bryen,

professor emerita, Temple

University, USA

This is a story bravely told of one man’s incredible endurance and fortitude against amazing odds. It will make you smile and weep, but most definitely it will restore you faith that all things are possible when you dream.

— Sandra Hartley, BSc.

MRCSLT, marketing

director, Logan

Technologies, Ltd.

It’s impossible to read this book without understanding just how much most of us take for granted.

— John-Paul Flintoff, author, How To Change The World

Martin’s writing makes you feel what he feels. He vividly reminds us of all those little injustices we each experienced that help us to grow and be stronger because of them. He reminds us that we all can grow from life’s twists if we choose to do so. Most important, Martin Pistorius shows us that God really does not give us more than we can handle, but rather he gives us the opportunity to meet adversity head on and overcome it no matter what the challenge.

Read Ghost Boy. It really is a “page turner” and you will be a better person for experiencing Martin Pistorius’ life.

— Michael Hingson, New York

Times best-selling author,

Thunder Dog

© 2013 by Martin Pistorius

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other—except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Nelson Books, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Nelson Books and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc.

Page design by Walter Petrie

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

Ghost Boy was previously published by Simon & Schuster Ltd, July 2012.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress

ISBN-13: 978-1-4002-0583-7

Printed in the United States of America

13 14 15 16 17 RRD 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my wife, Joanna, who listens to the whispers of my soul and loves me for who I am.

CONTENTS

Prologue

1 Counting Time

2 The Deep

3 Coming Up for Air

4 The Box

5 Virna

6 Awakening

7 My Parents

8 Changes

9 The Beginning and the End

10 Day by Day

11 The Wretch

12 Life and Death

13 My Mother

14 Other Worlds

15 Fried Egg

16 I Tell a Secret

17 The Bite

18 The Furies

19 Peacock Feathers

20 Daring to Dream

21 Secrets

22 Out of the Cocoon

23 An Offer I Can’t Refuse

24 A Leap Forward

25 Standing in the Sea

26 She Returns

27 The Party

28 Henk and Arrietta

29 The Healer

30 Escaping the Cage

31 The Speech

32 A New World

33 The Laptop

34 The Counselor

35 Memories

36 Lurking in Plain Sight

37 Fantasies

38 A New Friend

39 Will He Ever Learn?

40 GD and Mimi

41 Loving Life and Living Love

42 Worlds Collide

43 Strangers

44 Everything Changes

45 Meeting Mickey?

46 The Real Me

47 A Lion’s Heart

48 I Tell Her

49 Sugar and Salt

50 Falling

51 Climbing

52 The Ticket

53 Coming Home

54 Together

55 I Can’t Choose

56 Fred and Ginger

57 Leaving

58 A Fork in the Road

59 Confessions

60 Up, Up, and Away

61 Saying Goodbye

62 Letting Go

63 A New Life

64 Waiting

Acknowledgments

PROLOGUE

Barney the Dinosaur is on the TV again. I hate Barney—and his theme tune. It’s sung to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

I watch children hop, skip, and jump into the huge purple dinosaur’s open arms before I look around me at the room. The children here lie motionless on the floor or slumped in seats. A strap holds me upright in my wheelchair. My body, like theirs, is a prison that I can’t escape: when I try to speak, I’m silent; when I will my arm to move, it stays still.

There is just one difference between me and these children: my mind leaps and swoops, turns cartwheels, and somersaults as it tries to break free of its confines, conjuring a lightning flash of glorious color in a world of gray. But no one knows because I can’t tell them. They think I’m an empty shell, which is why I’ve been sitting here listening to Barney or The Lion King day in, day out for the past nine years, and just when I thought it couldn’t get any worse, Teletubbies came along.

I’m twenty-five years old, but my memories of the past only begin from the moment I started to come back to life from wherever I’d been lost. It was like seeing flashes of light in the darkness as I heard people talking about my sixteenth birthday and wondering whether to shave the stubble on my chin. It scared me to listen to what was being said because, although I had no memories or sense of a past, I was sure I was a child and the voices were speaking about a soon-to-be man. Then I slowly realized it was me they were discussing, even as I began to understand that I had a mother and father, brother and sister I saw at the end of every day.

Have you ever seen one of those movies in which someone wakes up as a ghost but they don’t know they’ve died

? That’s how it was, as I realized people were looking through and around me, and I didn’t understand why. However much I tried to beg and plead, shout and scream, I couldn’t make them notice me. My mind was trapped inside a useless body, my arms and legs weren’t mine to control, and my voice was mute. I couldn’t make a sign or a sound to let anyone know I’d become aware again. I was invisible—the ghost boy.

So I learned to carry my secret and became a silent witness to the world around me as my life passed by in a succession of identical days. Nine years have passed since I became aware once more, and during that time I’ve escaped using the only thing I have—my mind—and explored everything from the black abyss of despair to the psychedelic landscape of fantasy.

That’s how things were until I met Virna, and now she alone suspects there’s an active consciousness hidden inside me. Virna believes I understand more than anyone thinks possible. She wants me to prove it tomorrow when I’m tested at a clinic specializing in giving the silent a voice, helping everyone—from those with Down syndrome and autism to brain tumors or stroke damage—to communicate.

Part of me dares not believe this meeting might unlock the person inside the shell. It took so long to accept I was trapped inside my body—to come to terms with the unimaginable—that I’m afraid to think I might be able to change my fate. But, however fearful I am, when I contemplate the possibility that someone might finally realize I’m here, I can feel the wings of a bird called hope beginning to beat softly inside my chest.

1 COUNTING TIME

I spend each day in a care home in the suburbs of a large South African city. Just a few hours away are hills covered in yellow scrub where lions roam looking for a kill. In their wake come hyenas that scavenge for leftovers and finally there are vultures hoping to peck the last shreds of flesh off the bones. Nothing is wasted. The animal kingdom is a perfect cycle of life and death, as endless as time itself.

I’ve come to understand the infinity of time so well that I’ve learned to lose myself in it. Days, if not weeks, can go by as I close myself down and become entirely black within—a nothingness that is washed and fed, lifted from wheelchair to bed—or as I immerse myself in the tiny specks of life I see around me. Ants crawling on the floor exist in a world of wars and skirmishes, battles being fought and lost, with me the only witness to a history as bloody and terrible as that of any people.

I’ve learned to master time instead of being its passive recipient. I rarely see a clock, but I’ve taught myself to tell the time from the way sunlight and shadows fall around me after realizing I could memorize where the light fell whenever I heard someone ask the time. Then I used the fixed points that my days here give me so unrelentingly—morning drink at ten a.m., lunch at eleven thirty, an afternoon drink at three p.m.—to perfect the technique. I’ve had plenty of opportunity to practice, after all.

It means that now I can face the days, look at them square on and count them down minute by minute, hour by hour, as I let the silent sounds of the numbers fill me—the soft sinuousness of sixes and sevens, the satisfying staccato of eights and ones. After losing a whole week like this, I give thanks that I live somewhere sunny. I might never have learned to conquer the clock if I’d been born in Iceland. Instead I’d have had to let time wash over me endlessly, eroding me bit by bit like a pebble on the beach.

How I know the things I do—that Iceland is a country of extreme darkness and light or that after lions come hyenas, then vultures—is a mystery to me. Apart from the information that I drink in whenever the TV or radio is switched on—the voices like a rainbow path to the pot of gold that is the world outside—I’m given no lessons nor am I read to from books. It makes me wonder if the things I know are what I learned before I fell ill. Sickness might have riddled my body, but it only took temporary hostage of my mind.

It’s after midday now, which means there are less than five hours to go before my father comes to collect me. It’s the brightest moment of any day because it means the care home can be left behind at last when Dad comes to pick me up at 5 p.m. I can’t describe how excited I feel on the days my mother arrives after she finishes work at two o’clock.

I will start counting now—seconds, then minutes, then hours—and hopefully it will make my father arrive a little quicker.

One, two, three, four, five . . .

I hope Dad will turn on the radio in the car so that we can listen to the cricket game together on the way home.

“Howzat?” he’ll sometimes cry when a wicket is bowled.

It’s the same if my brother David plays computer games when I’m in the room.

“I’m going up to the next level!” he’ll occasionally shriek as his fingers fly across the console.

Neither of them has any idea just how much I cherish these moments. As my father cheers when a six is hit or my brother’s brow knits in frustration as he tries to better his score, I silently imagine the jokes I would tell, the curses I would cry with them, if only I could, and for a few precious moments I don’t feel like a bystander any more.

I wish Dad would come.

Thirty-three, thirty-four, thirty-five . . .

My body feels heavy today, and the strap holding me up cuts through my clothes into my skin. My right hip aches. I wish someone would lie me down and relieve the pain. Sitting still for hours on end isn’t nearly as restful as you might imagine. You know those cartoons when someone falls off a cliff, hits the ground, and smashes—kerpow!—into pieces? That’s how I feel—as if I’ve been shattered into a million pieces, and each one is hurting. Gravity is painful when it’s bearing down on a body that’s not fit for the purpose.

Fifty-seven, fifty-eight, fifty-nine. One minute.

Four hours, fifty-nine minutes to go.

One, two, three, four, five . . .

Try as I might, my mind keeps returning to the pain in my hip. I think of the broken cartoon man. Sometimes I wish I could hit the ground as he does and be smashed into smithereens. Because maybe then, just like him, I could jump up and miraculously become whole again before starting to run.

2 THE DEEP

Until the age of twelve, I was a normal little boy—shyer than most maybe and not the rough-and-tumble kind but happy and healthy. What I loved most of all was electronics, and I had such a natural ability with them that my mother trusted me to fix a plug socket when I was eleven because I’d been making electronic circuits for years. My flair also meant I could build a reset button into my parents’ ancient computer and rig up an alarm system to protect my bedroom from my younger brother and sister, David and Kim. Both were determined to invade my tiny Lego-filled kingdom, but the only living thing allowed to enter it, apart from my parents, was our small yellow dog called Pookie, who followed me everywhere.

Over the years I’ve listened well during countless meetings and appointments, so I learned that in January 1988 I came home from school complaining of a sore throat and never went back to classes again. In the weeks and months that followed, I stopped eating, started sleeping for hours every day, and complained of how painful it was to walk. My body began to weaken as I stopped using it and so did my mind: first I forgot facts, then familiar things like watering my bonsai tree, and finally even faces.

To try and help me remember, my parents gave me a frame of family photos to carry around, and my mother, Joan, played me a video of my father, Rodney, every day when he went away on business. But while they hoped the repetition might stop the memories slipping from my mind, it didn’t work. My speech deteriorated as I slowly forgot who and where I was. The last words I ever spoke were about a year after I first became ill as I lay in a hospital bed.

“When home?” I asked my mother.

But nothing could reach me as my muscles wasted, my limbs became spastic, and my hands and feet curled in on themselves like claws. To make sure I didn’t starve as my weight plummeted, my parents woke me up to feed me. As my father held me upright, my mother spooned food into my mouth, and I swallow

ed instinctively. Other than that, I didn’t move. I was completely unresponsive. I was in a kind of waking coma that no one understood because the doctors couldn’t diagnose what had caused it.

At first, the medics thought my problems were psychological, and I spent several weeks in a psychiatric unit. It was only when I was suffering from dehydration after the psychologists failed to persuade me to eat or drink that they finally accepted my illness was physical and not mental. So brain scans and EEGs, MRI scans and blood tests were done, and I was treated for tuberculosis and cryptococcal meningitis, but no conclusive diagnosis was made. Medication after medication was tried—magnesium chloride and potassium, amphotericin and ampicillin—but to no effect. I’d traveled beyond the realms of what medicine understood. I was lost in the land where dragons lie, and no one could rescue me.

All my parents could do was watch me slip away from them day by day: they tried to keep me walking, but I had to be held up as my legs got weaker and weaker; they took me to hospitals all over South Africa as test after test was run, but nothing was found; and they wrote desperate letters to experts in America, Canada, and England, who said their South African colleagues were surely doing all that could be done.

It took about a year for the doctors to confess that they had run out of treatment options. All they could say was that I was suffering from a degenerative neurological disorder, cause and prognosis unknown, and advise my parents to put me into an institution to let my illness run its course. Politely but firmly the medical profession washed its hands of me as my mother and father effectively were told to wait until my death released us all.

So I was taken home, where I was cared for by my mother, who gave up her job as a radiographer to look after me. Meanwhile my father worked such long hours as a mechanical engineer that he often didn’t get home to see David and Kim before they went to bed. The situation was untenable. After about a year at home, at the age of fourteen it was decided that I should spend my days in the care center where I am now, but I’d go home each night.

Ghost Boy

Ghost Boy