- Home

- Martin Pistorius

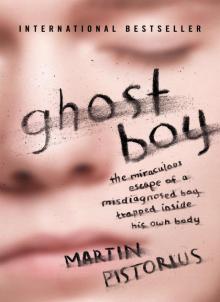

Ghost Boy Page 11

Ghost Boy Read online

Page 11

“Have you got lucky, Dave?” Dad asked with a smile as he got me out of the car.

“No!” Dave replied. “It’s my boss’s car. He was going away for the weekend with his wife, so I drove them to the airport, and I’m picking them up tomorrow.”

He and my father began to chat about events a world away as I was pushed inside.

“Have you seen the pictures on TV?” Dave asked my father. “It’s extraordinary.”

I knew what they were talking about. Princess Diana had been killed in a car crash, and the outpouring of emotion that had followed her death had been all over South African television screens. I’d watched the footage of flowers piled high in an English palace garden and thought about them now—such an outpouring of love for one woman, a person who had touched so many lives.

After Dave finished treating me, he said he would see me again the next week and then said goodbye. But two days later, Kim came to pick me up from the care center, and we got home to find our parents waiting. I knew instantly that something terrible had happened.

“Dave is dead,” my father said to Kim in a rush as she helped me out of the car.

I felt a pain in my chest as I listened to my parents tell Kim what had happened. The previous night Dave and Ingrid had got into the Mercedes to drive to the airport to pick up Dave’s boss and his wife just as they’d promised. But as they’d reversed out of their gate, some men had jumped in front of them and demanded the car. In the beam of the headlights, Dave and Ingrid could see the men had guns.

The robbers also wanted their jewelry and Dave had silently handed them his watch and wedding ring, hoping it might be enough to persuade them to go. But suddenly, without warning, one of the men pulled the trigger, and a single shot went through Dave’s forehead. As he slumped forward, another car pulled up, which the robbers jumped into. Dave survived for just a few hours after being airlifted to hospital.

“It’s so terrible,” my mother said sadly. “How could they do it? He was such a good man.”

I felt breathless as I heard the news, unable to believe Dave’s life had been ended so brutally. I thought how unfair it was that I’d clung onto mine even when I hadn’t wanted it at times, and yet Dave, who had loved his so much, had lost it. Then I thought of Ingrid, and the love that had been extinguished by a bullet. I still didn’t fully understand what I’d seen between her and Dave so many months before, but instinctively I knew her grief for its loss would be almost unbearable. The men were never caught.

30 ESCAPING THE CAGE

Learning to communicate is like travelling along a road only to find the bridge you need to cross the river has been washed away. Even though I have thousands of words on my grids now, there are still ones I think of but don’t have. And when I do have them, how do I take a thought and put it into symbols or feel an emotion and trap it on a screen? Talking is about so much more than words, and I’m finding the ebb and flow, rhythm, and dance of it almost impossible to master.

Just think of the man who raises his eyebrows when the waiter gives him the restaurant bill for the anniversary dinner he’s just had with his wife.

“You’ve got to be joking!” he says as he looks at it.

As his wife listens, she’ll know from his tone and look whether his words are an angry accusation about money he begrudges or an affectionate ribbing of the woman he would spend his last penny on. But I can’t spit out syllables in anger or shriek them happily; my words will never quaver with emotion, rise expectantly for a laugh just before a punch line, or drop dangerously in anger. Instead I deadpan each and every one electronically.

After tone, comes space. I used to spend hours daydreaming what I’d say or having endless conversations in my head. But now that I’m able to talk, I don’t always get the chance to say what I want to. A conversation with me is slow and takes time and patience that many people don’t have. The person I talk to must sit and wait while I input symbols into my computer or point to letters on my alphabet board. People find the silence so hard, they often don’t talk to me.

I’ve been working now for more than six months; I have friends and colleagues; I meet strangers when I go out into the world; and I’m interacting with them all. In doing so, I’ve learned that people’s voices move in a seamless cycle, sentences running one into another while they talk. But I interrupt the rhythm and make it messy. People must make a conscious effort to look at me and listen to what I have to say. They must allow me the space to speak because I can’t butt in, but many don’t want to listen to the silence I create. I understand why, because we live in a world in which we seldom hear nothing at all. There is usually a television or radio, telephone or car horn to fill the gaps, and if not there is meaningless small talk. But a conversation with me is as much about the silences as it is about the words, and I notice if my words are listened to or not because I choose each one so carefully.

I’m not nearly as talkative as I once thought I would be. When my family chat over dinner, I often stay silent, and when colleagues talk about what they did on the weekend, I sometimes don’t join in. People don’t mean to be unkind; they just don’t think to stop and give way to me. They assume I’m taking part in their conversation because I’m in the same room, but I’m not. The best time for me to talk is with one person who knows me well enough to pre-empt whatever I’m going to say.

“You want to go to the cinema?” Erica will say as I point to “C” and “I.”

“You think she’s cute?” she’ll ask when I smile at a woman who passes.

“Water?” she’ll declare when I bring my drinks grid up on my laptop.

I like it when Erica does this because I’m as keen to take shortcuts as anyone else. Just because my life is lived as slowly as a giant toddler who needs diapers, bottles, straws, and a sunhat before he can step foot outside the house doesn’t mean I enjoy it that way. That’s why I’m glad when people who know me well help me to speed up a little. They don’t seem to worry that I’ll be offended if they butt in while we talk. If only they knew what I would give to enjoy the rapid cut and thrust of the conversations I hear around me.

I often wonder if people think I have any sense of humor at all. Comedy is all in the timing, the rapid delivery, and arched eyebrow, and I might just manage the last of that trio, but the first two are a serious problem for me. People have to know me well to know that I enjoy joking around, and the fact that I’m often so silent means it’s easy for them to assume I’m serious. It feels at times as if I’m still someone others create their own character for, just as I was during all the years when I couldn’t communicate. I remain in so many ways a blank page on to which they write their own script.

“You’re so sweet,” people will often say.

“What a gentle nature you have!” person after person tells me.

“You are such a kind man,” someone else trills.

If only they knew of the gnawing anxiety, fiery frustration, and aching sexual desire that course through my veins at times. I’m not the gentle mute they often think I am; I’m just lucky that I don’t unwittingly betray my feelings by snapping in anger or whining in annoyance. So often now I’m aware that I’m a cipher for what other people want to think of me.

The only time I can guarantee people will be keen to know what I’m saying is when I’m not actually talking to them. Children aren’t the only ones who reveal their inbuilt voyeurism by staring—adults just hide it better. I’m often stared at as I spell out words on my alphabet board with hands that are still perhaps the most capricious part of my body. While my left hand remains largely unreliable, I can use my right to point at the letters on my alphabet board and operate my computer switches. But I can’t hold firmly onto something like a mug. Even though I can lift finger food to my mouth, I can’t hold an interloper like a fork for fear I might stab myself because my movement is so jerky. At least I’m getting so fast at using my board now that strangers find it harder and harder to look over my shoulder and lis

ten in.

“He goes too quickly for me!” my mother said with a laugh to a man who’d been staring at us as we chatted in a supermarket queue.

The man looked embarrassed as Mum spoke to him, obviously fearful that he was going to be chastised. But we are so used to being listened to that neither my mother nor I take much notice any more. Despite these difficulties in communicating, I still treasure the fact that I was given the chance to speak at all. I was given an opportunity that I took, and without it I wouldn’t be where I am now. My rehabilitation is the work of many people—Virna, my parents, the experts at the communication center—because I would never have been able to talk without their help. Others are not so lucky.

Recently, in the same supermarket where the man tried to listen to my conversation with Mum, we saw an older woman being pushed around in a wheelchair. She looked about fifty. Soon my mother started chatting to her and her caregiver. Maybe the woman was using sign language or pointing at things but for some reason my mother discovered that she’d lost the power of speech after a stroke.

“Does your family know about all the things that can be done to help you communicate again?” Mum asked the woman before showing her my alphabet board. “There’s so much out there, but you have to find it.”

The caregiver told us the woman had an adult daughter. Mum urged her to explain that she’d met someone who had told her about all the things that could be done for her mother.

“There’s no reason why you shouldn’t be able to communicate with your daughter again,” Mum said to the woman. “You just have to find out what works best for you.”

But when we next met, the caregiver told us that the woman’s daughter hadn’t done anything about what she’d been told.

“Why don’t you give me her phone number?” Mum said. “I’d be happy to reassure her that she mustn’t give up hope or listen to what the doctors say.”

As the caregiver wrote out the phone number on a piece of paper, I looked at the woman sitting opposite me in her chair.

“G-O-O-D-L-U-C-K,” I spelled out on my alphabet board, and she stared at me for the longest moment.

A few days later Mum came back into the living room after calling the woman’s daughter.

“I don’t think she really wanted to hear from me,” she said. “She just didn’t seem interested.”

We said no more about it. We both knew that the woman would never escape the straitjacket of her own body—she wasn’t going to be given the chance to. She’d be silent forever because no one was going to help set her free.

After that, I often thought about the woman and wondered how she was. But whenever I did, I remembered her eyes as she looked at me the last time I saw her in the supermarket. They’d been filled with fear. Now I understood why.

31 THE SPEECH

I can hardly believe I’m here. It’s November 2003 and I’m sitting on a low stage in a huge lecture room with my colleague Munyane, who has just addressed the audience in front of us. There must be more than 350 people waiting for me to speak. I’ve been working at the communication center for four months and have been chosen to address a conference of health professionals.

First Munyane gave an overview of AAC, and now it’s my turn to talk. Even though all I must do is press the button that will make Perfect Paul’s voice boom out of the sound system to which my laptop is connected, I don’t know if I’ll be able to do it. My hands are shaking so much I’m not sure I’ll be able to control them.

Somehow I’ve become an accidental public speaker in recent months, and my story has even been featured in the newspapers. While it has surprised me that a room full of people at a school or community center want to hear about me, I can’t think why so many have come today. I wish Erica were here to give me a smile. She’s gone back to the States, and it’s in moments like this that I miss her most. The friendship I treasured so much must now be contained in emails, and the door she gave me into the world has closed.

I should have known this was a big event when Mum and I arrived and were offered lunch from a table covered in more dishes than I’d ever seen before. The prospect of picking exactly what I wanted to eat was almost too much for me, and the sticky toffee pudding I’d finished my meal with rolls uneasily in my stomach now as I stare out into the audience.

Munyane smiles.

“They’re ready when you are,” she whispers.

I push the tiny lever that controls my new electric wheelchair and glide to the center of the stage. Just as Professor Alant predicted, it has made me far more independent. A month before my twenty-eighth birthday, I was finally able to control where I went and when for the first time. Now if I want to leave the room because the television is boring, I can go; if I decide to explore the streets around the house where my parents have lived since I was a child; then I’m able to.

I got the chair after writing an open letter on a website I belong to asking for any suggestions about how to get one because I knew my parents couldn’t afford the cost. Over the past few months I’ve made friends in countries like England and Australia by joining Internet groups and meeting more people in the AAC community. It’s a strange but reassuring feeling to know that I have friends in so many places now. Getting to know people via my computer feels liberating. I’m exploring the world, and the people I meet don’t see my chair: they just know me.

But I never expected the Internet to be as powerful as it turned out to be after my letter was seen by someone in Canada who had a relative living not far from me in South Africa. Soon he had contacted me to say that his Round Table group wanted to buy me a new chair with some of the money they’d raised for charity. Words can’t express how grateful I am to have it; even though I’m not sure everyone around me is quite so pleased.

Controlling my own movement for the first time is interesting, as I totter like a toddler learning to move independently. I’ve crashed into doors, fallen off pavements, and run over the toes of unsuspecting strangers as I’ve revelled in my new-found liberation.

I’ve become more independent in other ways too. My colleague Kitty, who is an occupational therapist, has worked with me on tiny details that have made my work life easier. Now I have a new handle on my office door, which means I can open it without help. I’ve also started wearing weights on my wrists to try to strengthen my muscles and stabilize my hand tremors. I continue to be well acquainted with drinking yogurt, which means no one has to feed me at lunchtime, and I’m careful never to ask for tea or coffee unless someone offers because I’m determined not to be a drain on anyone. As for my clothes, I’m wearing a shirt and tie today. Soon I’m hoping to get my first suit.

Life is changing in so many ways, but perhaps none is more terrifying than this. I look out at the audience again and force myself to breathe deeply. My hands are trembling, and I will them to let me control my laptop. Turning my head slowly to the left, I shine the headmouse’s infrared beam onto the screen and click on one of my switches.

“I would like you all to stop for a moment and really think about not having a voice or any means to communicate,” my computer voice says. “You could never say, ‘Pass the salt’ or tell someone the really important things like ‘I love you.’ You can’t tell someone that you’re uncomfortable, cold, or in pain.

“For a time, when I first discovered what had happened to me, I went through a phase where I would bite myself in frustration at the life I found myself in. Then I just gave up. I became totally and completely passive.”

I hope the pauses I programmed into my speech are enough to help the audience follow what I’m saying. It’s hard to listen to synthesized speech when you are used to voices that pause, rise, and fall. But there’s nothing more that I can do now. The room is quiet as I talk about meeting Virna and my assessment, the hunt for a communication device, and the cancellation of the black box. Then I tell them about the months of research into computer software, the money my grandfather GD left to my father when he died that allowe

d my parents to buy me equipment, and the work I’ve done learning to communicate.

“In 2001 I was at a day center for the profoundly mentally and physically disabled,” I say. “Eighteen months ago, I didn’t know anything about computers, was completely illiterate, and had no friends.

“Now I can operate more than a dozen software programs, I’ve taught myself to read and write, and I have good friends and colleagues at both of my two jobs.”

I stare out at the rows of faces in front of me. I wonder if I’ll ever be able to convey my experiences to people. Is there a limit to words? A place where they can take us after which there is a no man’s land of incomprehension? I can’t be sure. But I must at least hope that somehow I can help people to understand if they want to. There are so many eyes on me, hundreds of pairs, and my heart thumps as my computer carries on speaking.

“My life has changed dramatically,” I say. “But I’m still learning to adjust to it, and although people tell me that I’m intelligent, I struggle to believe it. My progress is down to a lot of hard work and the miracle that happened when people believed in me.”

As I timidly look out at the room, I realize that no one is fidgeting or yawning. Everyone is completely still as they listen.

“Communication is one of the things that makes us human,” I say. “And I am honored to have been given the chance to do it.”

Finally I fall silent. My speech is over. I’ve said all that I wanted to say to this room full of strangers. They are silent for a split second. I stare out at them, unsure what to do. But then I hear a noise—the sound of clapping. It’s soft at first but the hands beat together louder and louder, and I watch as first one person and then another get to their feet. One by one, the crowd rises. I stare at the faces in front of me, people smiling and laughing as they clap, while I sit in the middle of the stage. The sound swells and swells. Soon it’s so big that I feel it might suck me under. I stare down at my feet, hardly daring to believe what I’m seeing and hearing. Finally I push the lever of my chair and move to the side of the stage.

Ghost Boy

Ghost Boy