- Home

- Martin Pistorius

Ghost Boy Page 3

Ghost Boy Read online

Page 3

I look at her. Tears glimmer silver in the corners of her eyes. Her faith in me is so strong I must repay it.

6 AWAKENING

Two glass doors slide open in front of me with a hiss. I’ve never seen doors like this before. The world has surprised me again. I sometimes see it as it passes the window of a car I’m sitting in, but other than that I remain separate from it. The small glimpses I have of the world always intrigue me. I once spent days thinking about a doctor’s mobile phone after seeing it clipped to his belt: it was so much smaller than Dad’s that I couldn’t stop wondering what kind of battery was powering it. There are so many things I wish I could understand.

My father is pushing my wheelchair as we enter the Center for Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Pretoria. It is July 2001—thirteen and a half years since I first fell ill. On the pavement outside, I saw students walking along in the sunshine and jacaranda trees arching overhead, but everything is quiet inside the building. Sea green carpet tiles stretch down a corridor; the walls are covered in information posters. We are a small band of explorers entering this unknown world: my parents, my brother David, and Virna, plus Marietta and Elize, a caregiver and physiotherapist who have known me for years.

“Mr. and Mrs. Pistorius?” a voice asks, and I raise my eyes to see a woman. “My name is Shakila, and I’ll be assessing Martin today. We’re just getting the room ready, but it won’t be long.”

Fear washes cold over me. I can’t look into the faces around me; I don’t want to see the doubt or hope in their eyes as we silently wait. Soon we’re ushered into a small room where Shakila is waiting with another woman called Yasmin. I hang my head as they start talking to my parents. The inside of my cheek feels sore. I accidentally bit myself as I was fed my lunch earlier today, and my mouth still feels tender even though the bleeding has stopped.

As Shakila asks my parents about my medical history, I wonder what they’re thinking after all this time. Do they feel as afraid as I do?

“Martin?” I hear a voice say, and my wheelchair is pushed across the room.

We come to rest in front of a large sheet of acrylic glass suspended on a metal stand directly in front of me. Red lines criss-cross the screen, dividing it into boxes with small black and white pictures stuck in some of them. These line drawings show simple things—a ball, a running tap, a dog—and Shakila stands on the other side of the screen watching me intently as I stare at them.

“I want you to look at the picture of the ball, Martin,” Shakila says.

I raise my head a little and let my eyes search the screen. I can’t control my head enough to move it properly from side to side, so my eyes are the only part of my body that I’m totally the master of. They slide back and forth across the pictures until I find the ball. I fix my eyes on it and stare.

“Good, Martin, that’s very good,” Shakila says softly as she looks at me.

I feel afraid suddenly. Am I looking at the right picture? Are my eyes really fixed on the ball or are they looking at another of the symbols? I can’t be sure.

“Now I want you to look at the dog,” Shakila says and I start to search again.

My eyes move slowly over the pictures, not wanting to make a mistake or miss a thing. I search slowly until I find the cartoon dog to the left of the board and look at it.

“And now the television,” she says.

I soon find the picture of the television. Although I want to keep staring at it to show Shakila that I’ve found what she’d asked me to, my chin drops towards my chest. I try not to panic as I wonder if I’m failing the test.

“Shall we try something different?” Shakila asks and my wheelchair is pushed towards a table covered in cards.

Each one has a word and a picture drawn on it. Panic. I can’t read the words. I don’t know what they say. If I can’t read them, will I fail the test? And if I fail the test, will I go back to the care home and sit there forever? My heart starts to thump painfully inside my chest.

“Can you point to the word “Mum” please, Martin?” Yasmin, the other speech therapist, asks me.

I don’t know what the word “Mum” looks like but even so I stare at my right hand, willing it to move, wanting it to make some small sign that I understand what I’m being asked. My hand trembles furiously as I try to lift it from my lap. The room is deathly silent as my arm slowly lifts into the air before jerking wildly from side to side. I hate my arm.

“Let’s try again, shall we?” Shakila says.

My progress is painfully slow as I’m asked to identify symbols by pointing at them. I feel ashamed of my useless body and angry that it can’t do better the first time anyone asks anything of it.

Soon Shakila goes to a large cupboard and pulls out a small rectangular dial. It has more symbols on it and a large red pointer in the middle. Shakila sets it on the table in front of me before plugging in some wires that run from a yellow plate fixed to the end of a flexible stand.

“This is a dial scan and a head switch,” Yasmin explains. “You can use the yellow switch to control the pointer on the scan as it goes around and stop it to identify the symbol you want. Do you understand, Martin? Can you see the symbols on the scan?

“When we ask you to identify one, we want you to push your head against the switch when the pointer reaches the symbol. Do you think you can do that?”

I look at the symbols: one shows water running from a tap, another a plate of biscuits, a third a cup of tea. There are eight symbols in total.

“I want you to stop the pointer when it reaches the tap, please,” Yasmin says.

The red pointer starts to inch around the dial. It goes so slowly that I wonder if it’ll ever reach the picture of the tap. Slowly it drags its way around the dial and I watch until it nears the tap. I jerk my head against the switch. The pointer stops at the right place on the dial.

“Good, Martin,” a voice tells me.

Amazement fills me. I’ve never controlled anything before. I’ve never made another object do what I wanted it to. I’ve fantasized about it again and again, but I’ve never raised a fork to my mouth, drunk from a cup, or changed TV channels. I can’t tie my shoes, kick a ball, or ride a bike. Stopping the pointer on the dial makes me feel triumphant.

For the next hour, Yasmin and Shakila give me different switches to use as they try to find out if there is any part of my body that I can control enough to use switches properly. My head, knee, and rebellious limbs are all put close enough to switches for me to try to make contact with them. First there’s a black rectangular box with a long white switch that sits on the side of the table in front of me. It’s called a wobble switch. I pull my right arm up before jerking it down, hoping to make contact with the switch, and knowing it’ll be by luck rather than judgement if I do. Then there is a huge yellow switch, as big and round as a saucer, that I flail my unruly right hand near because my left is almost completely useless. Again and again Yasmin and Shakila ask me to use the switches to identify simple symbols: a knife, a bath, a sandwich—the easiest kind of pictures, which even those with the lowest intelligence can identify. Sometimes I try to use my right hand, but more often I stare at the symbol I’m being asked to pick out.

After what feels like forever, Shakila finally turns to me. I’m looking intently at a symbol that shows a big yellow swirl.

“Do you like McDonald’s?” she asks.

I don’t know what she’s talking about. I can’t turn my head or smile to answer yes or no because I don’t understand the question.

“Do you like hamburgers?”

I smile at Shakila to let her know that I do, and she gets up. Going back to the large cupboard, she pulls out a black box. The top is divided into small squares by an overlying plastic frame, and inside each one I can see a symbol.

“This is a communication device called a Macaw,” Shakila tells me softly. “And if you can learn to use switches, then you might be able to use one of these some day.”

>

I stare at the box as Shakila turns it on, and a tiny red light flashes slowly in the corner of each square in turn. The symbols in the squares aren’t black and white like those on the cards. These are brightly colored, and there are words written next to them. I can see a picture of a cup of tea and a drawing of a sun. I watch Shakila to see what will happen next as she hits a switch to select a symbol.

“I am tired,” a recorded voice says suddenly.

It comes from the box. It’s a woman’s voice. I stare at the Macaw. Could this small black box give me a voice? I can hardly believe that anyone would think me capable of using it. Do they realize I can do more than point at a child’s ball drawn in thick black lines on a card?

“I’m sure that you understand us,” Shakila says as she sits in front of me. “I can see from the way your eyes travel that you can identify the symbols we ask you to, and you are trying to use your hand to do the same. I feel sure we’ll be able to find a way to help you communicate, Martin.”

I stare at the floor, unable to move any more today.

“Wouldn’t you like to be able to tell someone that you are tired or thirsty?” Shakila says softly. “That you would like to wear a blue sweater instead of a red one or that you want to go to sleep?”

I’m not sure. I’ve never told anyone what I want before. Would I be able to make choices if I was given them? Would I be able to tell someone that I want to leave my tea to cool instead of drinking it in hurried gulps when they lift a straw to my mouth because I know it’ll be the only opportunity I’ll have to drink for several hours? I know most people make thousands of decisions every day about what to eat and wear, where to go, and who to see, but I’m not sure I’ll be able to make even one. It’s like asking a child who has grown up in the desert to throw himself into the sea.

David (brother) and Martin

Martin

Martin

Martin’s dog Pookie

Martin and dad (Rodney)

Martin with plastic chicken—yay!

Mom (Joan) and David (brother) visiting Martin in the hospital with pneumonia

7 MY PARENTS

While my father’s faith in me has been stretched almost to breaking point, I don’t think it’s ever disappeared completely. Its roots were planted deeply many years ago when Dad met a man who’d recovered from polio. It had taken him a decade to get well again, but his experience convinced my father that anything was possible. Each day Dad has proved his faith in me in a string of tiny acts: washing and feeding me, dressing and lifting me, getting up every two hours throughout the night to turn my still body. A bear of a man with a huge gray beard like Father Christmas, his hands are always gentle.

It took time for me to realize that while my father looked after nearly all of my physical needs, my mother hardly came near me. Anger and resentment at what had happened poured out of her whenever she did. As time passed I saw that my family had been divided into two—my father and me on one side; my mother, David, and Kim on the other—and I realized that my illness had driven a deep wedge into the heart of a family I somehow instinctively knew had once been so happy.

Guilt filled me when I heard my parents arguing because I knew everyone was suffering because of me. I was the cause of all the bad feeling as my parents returned to the same battleground again and again: my mother wanted to put me into full-time residential care just as the doctors had advised; my father did not. She believed my condition was permanent and I needed so much special care that having me at home would harm David and Kim. My father, on the other hand, still hoped I might get better and believed it would never happen if I was sent away to an institution. This was the fundamental disagreement that reverberated through the years, sometimes as shouts and screams, sometimes as loaded silences.

For a long time I didn’t understand why my mother felt so differently to my father, but eventually I pieced together enough of the facts to realize that she had almost been destroyed by my illness, and she wanted to protect David and Kim from a similar fate. She had lost one child, and she didn’t want her healthy surviving son and daughter to be hurt in any way.

It hadn’t always been this way. For the first two years of my illness, my mother searched as tirelessly as my father for a cure to save the son she thought was dying as he slipped a little more out of their reach every day. I can’t imagine how my parents suffered as they watched their healthy child disappear as they pleaded with doctors, watched me being given medications, and agreed to have me tested for everything from tuberculosis of the brain to a host of genetic disorders only to be told that nothing could help me.

When traditional medicine ran out of answers, my mother wasn’t prepared to give up. For a year after the doctors told my parents they didn’t know how to treat me, she cared for me at home and tried everything from having me prayed over by faith healers to intensive vitamin regimens in the hope of helping me. Nothing worked.

My mother was tortured by her growing guilt that she hadn’t been able to save me. She was sure she had failed her child and felt increasingly desperate as her friends and family stayed away—some because they found my undiagnosed illness frightening, others because they were unsure how to comfort people who were facing any parents’ worst nightmare. Whatever their reason, people kept their distance as they hugged their healthy children close to them in silent gratitude, and my family became more and more isolated.

My mother’s unhappiness soon spiralled so badly out of control that she tried to commit suicide one night about two years after I first fell ill. After taking handfuls of pills, she lay down to die. But as she did so, Mum remembered what her mother had once told her about her father’s sudden death of a heart attack: he’d never said goodbye. Even in her fog of despair, my mother wanted to tell my father one last time how much she loved us all, and this saved her. When Dad realized what she’d done, he put her into the car with David, Kim, and me, and one of David’s friends who was staying the night, and drove us all to the hospital.

The doctors pumped Mum’s stomach, but after that night my brother’s friend was never allowed to stay again, and the isolation that my parents felt started to infect my younger brother and sister. They, too, suffered while my mother was treated on a psychiatric ward. By the time she came home, her doctors had decided that she could no longer help care for me. According to them, she was mourning the loss of her child and should have as little as possible to do with me to avoid further upset. She—ill, grief stricken, and desperate—took the doctors at their word and concentrated on caring for her two healthy children and returning to work full-time once she was well enough. Meanwhile, my father held down a demanding job and looked after me, for the most part, singlehandedly.

It was like this for many years, but gradually the situation has changed as my mother has softened and become more involved in my care. Now she looks after me almost as much as my father does, makes me the spaghetti and mince with peach chutney that she knows I like, and sometimes even lays my head on her lap if I’m lying on the sofa. It makes me happy to know that she can touch me now after shying away for so long, just as it makes me sad when I hear her playing music late at night because I know that sorrow is filling her as she listens to lyrics and remembers the past.

Sadness fills me too when I think of my father, who buried his ambitions, lost out on promotions, and took demotions to care for me. Each person in my family—my parents, brother, and sister—has paid a high price for my illness. While I can’t be sure, I sometimes wonder if all these lost hopes and dreams are the reason why a man as intelligent as my father has learned to hide his emotions so deeply that I sometimes wonder if he knows where they are anymore.

8 CHANGES

They call it the butterfly effect: the huge changes that a pair of silken wings can create with an almost imperceptible flutter. I think a butterfly is beating its wings somewhere in my life. To the outward eye, things have hardly changed since I was assessed: I still go to my care center each morning

and sigh gratefully when the afternoon comes to an end and I can go home to be fed, washed, and prepared for bed. But monotony is a familiar foe, and even the subtlest changes in it are noticeable.

The various care staff I see at my day center, during appointments for physio, or with doctors at the hospital don’t seem overly worried an expert has said I might soon be able to communicate. Considering some of the things I’ve seen, I’m surprised some of them aren’t a little more concerned. But I can certainly feel a change in the way my parents are speaking to me since I was assessed by the speech therapists. When Mum asks if I’ve had enough food, she waits just a little longer for my head to jerk its way down or my mouth to smile. My father talks to me more and more now as he brushes my teeth at night. The changes are so small that my parents might not even be aware of them, but I can sense hope in the air for the first time in years.

I’ve heard enough of what they’ve said to know that if I’m to start communicating properly it will be at the most basic level. This will not be a Hollywood movie with a neat happy ending or a trip to Lourdes where the mute are miraculously given a voice. The speech therapists’ report has recommended that my mother and father start trying to communicate with me in the tiniest of ways. Apparently my head jerk and smile are not as reliable as I thought they were, and I must learn a more consistent way to signal yes and no. Because my hands are too unruly to point properly, the best way for me to start “speaking” is by staring at symbols.

I’ll use symbols because I can’t read or write. Letters have held no meaning for me since I came back to life. Pictures will rule my life from now on: I’m going to live and breathe them as I learn their language. My parents have been told to make me a folder of words and their corresponding symbols. “Hello” is a picture of a stick man waving his hand, “like” is his face up close with a huge grin, and “thank you” is a drawing of an egg-shaped face with two hands held flat just below the mouth.

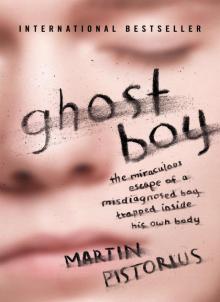

Ghost Boy

Ghost Boy